One gene may be key to coveted perfect pitch

A tantalizing headline for a musical biologist, about a new study published in PNAS:

Dichotomy and perceptual distortions in absolute pitch ability

E. Alexandra Athos, Barbara Levinson, Amy Kistler, Jason Zemansky, Alan Bostrom, Nelson Freimer & Jane Gitschier.

PNAS 11 September 2007 104(37): 14795-14800

Disappointingly, this study in no way tested a genetic basis for perfect pitch - no DNA was cloned or sequenced, no family trees analyzed, nothing that might actually help to identify a gene for perfect pitch. This is a typical case of the headline not representing the content of the study. The authors only make this surmise based on a bimodal distribution (either you have it or you don't), rather than perfect pitch being one extreme of a continuous variation in pitch perception ability. There could well be some genetic basis of absolute pitch perception, but other mechanisms could conceivably give the same bimodal distribution, such as having a specific development window of opportunity for nurturing this ability. Perhaps we are all born with the inherent capability to perceive absolute pitch, but without conscious training at a specific point in our brain development, the neural connections are not stabilized, and the ability is lost.

In any case, this is a very nice study. It shows a systematic bias towards erring on the sharp side with increasing age, suggesting possible mechanical changes in the cochlea, like altered elasticity of the membrane or reduction in the density of hair cells.

What was really interesting to me was the distribution of accuracy in note perception. Subjects with absolute pitch uniformly nailed the A and had high reliability on other 'white key' notes, but there were subtle yet systematic errors in identifying the 'black key' notes. The authors propose a kind of 'magnet' effect around A, due to heightened perception caused by orchestras tuning to A at various pitch standards, which is an intriguing idea, but remains to be tested.

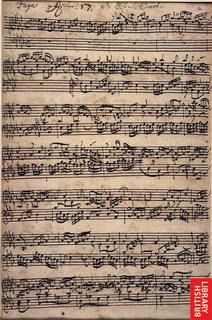

These systematic variations in perception, even in people with perfect pitch, could actually tell us as much about our tuning system as about the neurobiology of pitch perception. Our standard equal tempered tuning forces our scale into evenly sized intervals, rather than optimizing the primary intervals depending on the key of the music, as with various just tuning systems. Just temperament, as Bach so beautifully demonstrated with his Well Tempered Clavier (generally incorrectly descibed as modern equal temperament), brings out different 'colours' in the harmonies of each different key, when played on an appropriately tuned keyboard.

So I wonder: is the relative difficulty in identifying chromatic pitches a consequence of being habituated to music with a compromised equal tuning system? What would this study have measured in 18th century musicians, or in people brought up listening to non-western music, based on entirely different scales?

Proponents of just temperament have argued that we have done music a huge disservice by switching from just to equal temperament. Here is an excerpt from composer Kyle Gann's Just Intonation Explained pages:

...equal temperament chords do have a kind of active buzz to them, a level of harmonic excitement and intensity. By contrast, just-intonation chords are much calmer, more passive; you literally have to slow down to listen to them. (As Terry Riley says, Western music is fast because it's not in tune.) ... I've learned to hear equal temperament music as a kind of aural caffeine, overly busy and nervous-making. If you're used to getting that kind of buzz from music, you feel the lack of it as a deprivation when it's not there. But do we need it? Most cultures use music for meditation, and ours may be the only culture that doesn't. With our tuning, we can't. My teacher, Ben Johnston, was convinced that our tuning is responsible for much of our cultural psychology, the fact that we are so geared toward progress and action and violence and so little attuned to introspection, contentment, and acquiesence. Equal temperament could be described as the musical equivalent to eating a lot of red meat and processed sugars and watching violent action films. The music doesn't turn your attention inward, it makes you want to go out and work off your nervous energy on something.

Perhaps this study provides the first biological evidence that equal temperament doesn't quite resonate naturally with our brains.